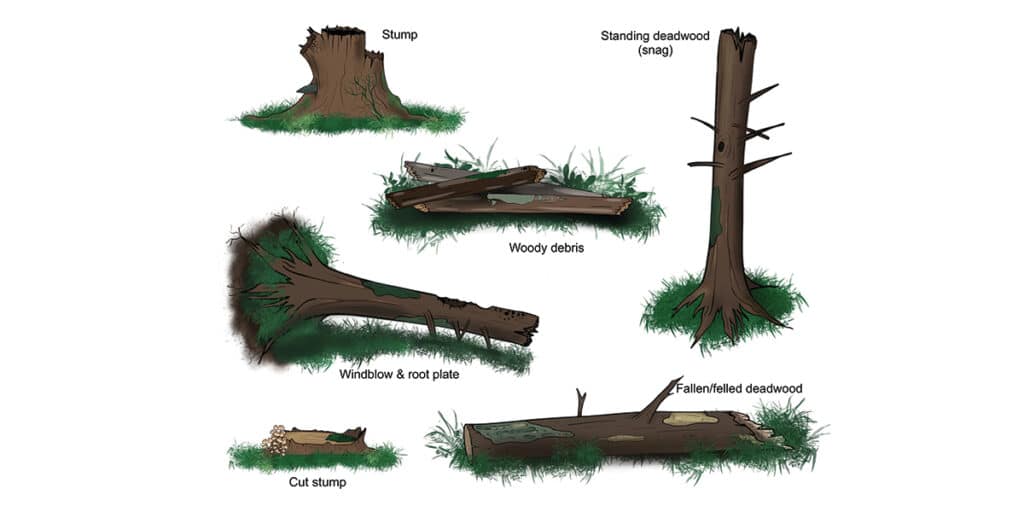

Deadwood comes in many different forms, from fallen timber decaying on the ground, dead limbs in the canopy, to rotting cores of ancient trees.

Deadwood has, historically, been removed from woodlands due to felling and extraction for timber production and firewood or to improve access, appearance and health. However, it plays a vital role in all woodlands and should be retained where possible and safe to do so.

As wood rots and decays, it passes nutrients back into the soil, in turn providing nourishment for growing plants and fungi, almost like a slow-release fertiliser.

Without the cycling of nutrients from fallen leaves and rotting wood, woodland soils would run out of these resources that are essential for plant growth.

As trees grow, they lock carbon into their structure. Deadwood therefore acts as a carbon store until it decays and is absorbed back into the soil.

Deadwood, particularly large pieces, also provides a unique habitat. The decaying structures create ‘microhabitats’ – tiny areas of different environments – for plants, fungi and animals to live and develop.

Although fungi and bark-eating beetles are the most commonly associated species, lichens and mosses, as well as cavity-nesting birds and bats, can be strongly dependent on deadwood.

The species found in and around deadwood will vary depending on the age, size and location of the wood, with different species preferring different stages of decomposition.

As a result, this decaying wood becomes a rich resource of food for wild birds and gamebirds alike. This reliable food source can enable young birds to become less dependent on supplementary feeding and have a broader, natural diet as adults, resulting in enhanced survival.